It was 2017. Woodbury’s Kate Swenson pulled into a parking spot at work, turned a camera on herself and hit the record button. She had to talk, she had to share and she had to cry.

“I want to talk about something that I think all my autism parents will understand,” says Swenson. “I want to talk about the last time.”

The “Last Time” talk lasted just over seven minutes and can easily be found with a Google search. Swenson covered everything from hoping her son, Cooper, 11, who has severe, nonverbal autism, would someday become a doctor or lawyer, to coming to the realization that neither would ever happen. She then talked of standing in line waiting to see Elmo. As she was holding her screaming 65-pound son, she caught, in the corner of her eye, a group of parents holding their precious babies.

She talked of an autism world where Cooper was safe, happy, healthy and joyful. She then talked of stepping out of that world and knowing that everything was about to change, ready or not.

For Swenson, it wasn’t OK. She says it wasn’t OK on that particular day; nor would it be tomorrow or the next day. At some point, Swenson went from dreaming about her son’s future, to worrying about his quality of life—this was her last time to think everything would be OK.

Locally, Swenson’s video went viral, having been viewed some 500,000 times. As it gained national attention and TV stations picked it up by the hundreds, the numbers grew exponentially.

“Across all platforms, it’s been viewed maybe 30 million times,” says Swenson. “Al Roker [NBC’s Today Show weather presenter] jokingly compared the numbers to the Super Bowl,” says Swenson.

Cooper’s Voice

Swenson has been writing on her blog, Finding Cooper’s Voice, about Cooper and the autism world he lives in since his diagnosis. “I was writing about disability before I knew about disability,” she says.

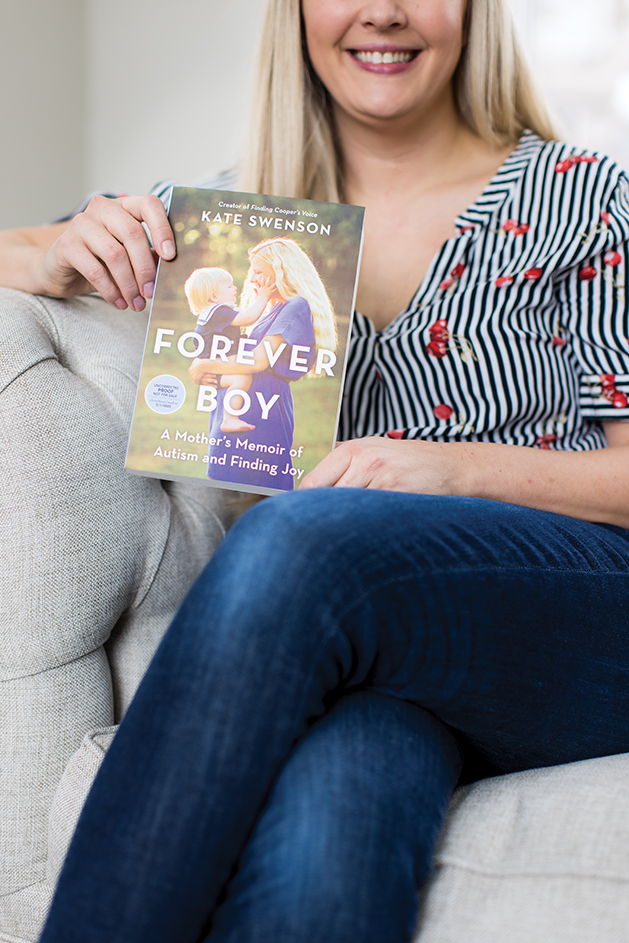

Her newest writing endeavor is her book, Forever Boy: A Mother’s Memoir of Autism and Finding Joy. (It was released on April 5, 2022.) “I signed the contract the Sunday our school emailed parents about going online because of COVID-19,” Swenson says. “I would have three kids at home and six months to write.”

Since its publishing? “I’m so incredibly proud of the book,” she says. The last part of its title, “Finding Joy,” came as a decree to those who read it.

“Waking up and looking for joy every day came after a series of epiphanies,” Swenson says. “The one that sticks in my mind happened while I was in the hospital on a cancer floor. These little girls were singing happy birthday to another little girl. That little girl had cancer, but the whole thing was just so joyful.”

That vision hit home for Swenson. “When I started looking for joy, I found more joy,” she says. “It varies, but I’m finding it.”

Gentle touches, silly smiles and genuine laughs are a few pieces of joy Swenson has found. Since then, the Find Cooper’s Voice Facebook page has welcomed visitors into the “Secret World of Autism.” It’s a catch all for Swenson’s stories, blog posts and videos. Some are happy; some are sad;

but everything is real.

Between Facebook and Instagram, this secret society has over one million followers. “The internet brings us all together,” Swenson says. “It’s universal.”

Like the “Last Time” video, content found on Finding Cooper’s Voice can be both resonating and polarizing. “You can hit lots of nerves,” Swenson says. At its best, it gives moms and dads living with autism a new neighbor. It’s another person who lives it; it’s another person who gets it.

At its worst, it’s ugly, it’s unfathomable and it’s vulgar. “There’s a lot ickiness,” Swenson says.

But Woodbury’s Rachel Flanagan, who found Swenson’s Facebook page shortly after her 4-year-old daughter received an autism diagnosis, says it’s been a wonderful resource.

“It’s one of the first resources I found,” Flanagan says. “Kate was talking about different ways to communicate, and she was doing the same things I was doing.” She likes the page because Swenson owns her journey.

“She tells you how she was feeling when something happened, how she’s feeling now and what she learned along the way,” Flanagan says. “She’s dedicated to the whole picture. She doesn’t just talk and write about where her son falls on the spectrum. She talks and writes about the whole spectrum. ”

Changing

“If you ask someone in their 70s about autism when they grew up, they’ll say they never saw it,” Swenson says. “They would be right. Back then, kids with autism were separated from everyone else.”

That’s not how autism looks today. “Kids with autism are in the schools. They’re out front and everyone is seeing them,” she says.

That’s kind of true. After Cooper was diagnosed with autism, his family moved from northern Minnesota to Cottage Grove and then to Woodbury. “We moved for services,” Swenson says. “The county where we lived had nothing.”

And now? “Cooper [now] has an amazing speech device,” Swenson says. “He uses sign language. He uses sounds and gestures, and he can do some typing.”

While she didn’t know it, Swenson would help with Flanagan’s search for services. “Minnesota is extraordinary with what it can offer,” Flanagan says. “But there’s a medical aspect you have to navigate, a school-district aspect you have to navigate and a family aspect you have to navigate.”

To find the way, it takes a village. Today, Flanagan’s village is Swenson’s subscriber group called Coop’s Troops. “It’s 4,000 [parents, grandparents, siblings, friends, teachers, therapists …] from around the world,” Swenson says. “We cry, we laugh and we get mad.”

Flanagan counts herself among the many. “It’s a safe community,” she says. “You can type things on the Coop’s Troops thread that you’d never type on a thread with 600,000 other people watching. If you want to show a bite mark and then ask why it’s not healing, you’ll have 40 people respond. If you say you haven’t slept in 48 [hours], they believe you.”

Two years ago, Flanagan attended a Coop’s Troops outing with 70 other women. “That day was better than years of therapy,” she says. “I left with a bunch of phone numbers in my phone, numbers I can use at 3 a.m.” She also left with the skills to change insurance and the confidence to change pediatricians. Talk of potty-training techniques and safe holds goes without saying. “They get it,” Flanagan says.

Moving forward

Swenson doesn’t know what will happen when her 65-pound little boy becomes a 180-pound man. She’ll still want to keep him safe, healthy and happy. She’ll still want him to be joyful. She’ll still want him to be OK.

And? “You’ll never again see me cry in my car on video,” Swenson says. That too, can be OK.

findingcoopersvoice.com

Finding Cooper’s Voice @findingcoopersvoice